Using foreign policy to reject deficit dogmatism

Speaking Security Newsletter | Advisory Note for Organizers and Candidates, n°37 | 20 August 2020

Situation

Biden’s top advisor recently said should he win, Biden would limit economic recovery in deference to the deficit. The Biden campaign has since issued a statement, (clumsily) backtracking, but there’s not much credence to the campaign’s response.

You don’t have to look that far back for a reason. Here’s Eric Levitz (full article, here), on how Democrats subjected the 2009 stimulus to the same brand of deficit dogmatism at play here:

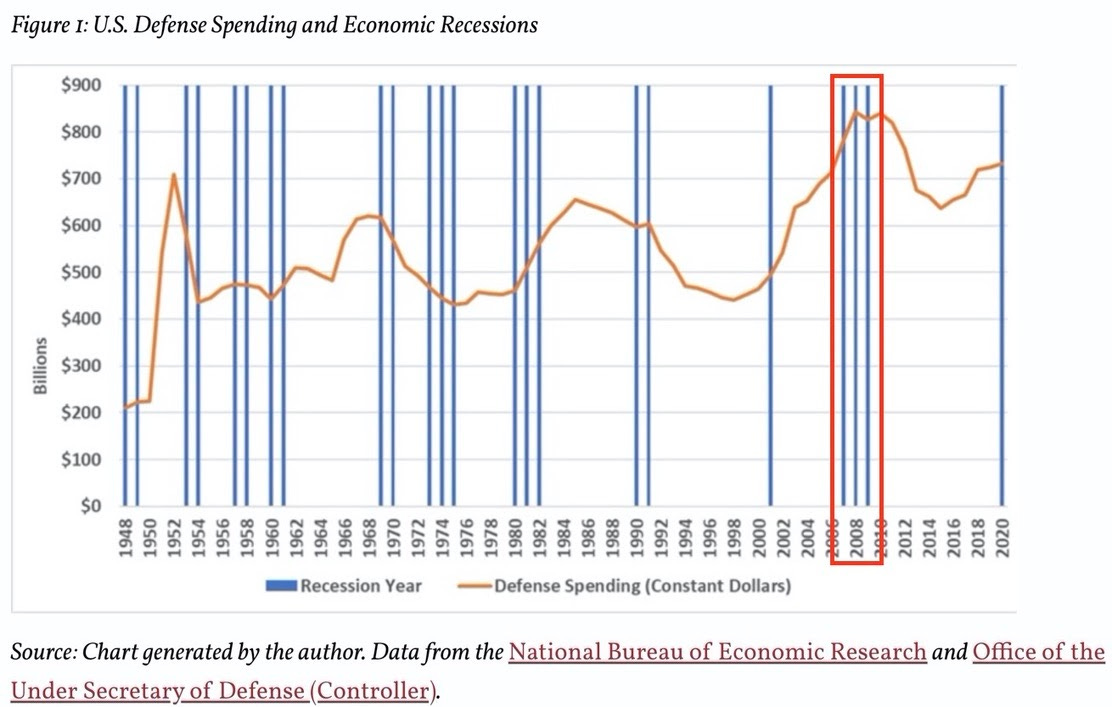

But defense spending was exonerated from Democrats’ reverence to austerity politics:

...and same with this recession. Democrats just (overwhelming) supported the latest iteration of Trump’s military budget ($740bn+, an increase over the previous year):

The political impact of shifting federal spending priorities

Here’s one way to use foreign policy to reject deficit dogmatism that exposes a concrete economic effect of the defense v. non-defense funding disparity. It builds on the language of the Pocan and Sanders amendments (10 percent conversion from defense budget to fund social programs) that rightly argue for a modest, positive shift in our abhorrent spending priorities.

Addendum to the Pocan/Sanders amdt. language: The 547,600 jobs* that members effectively voted against creating by opposing the amendments.

*This figure refers to the number of jobs created by a $74 billion investment in healthcare over the employment output from an equal amount obligated for defense. You’ll get similar results for investments in green energy, education, or any other sector — defense spending is by far the least useful thing you can with public funds w/r/t creating jobs.

The economic/political impact of the proposed conversion wasn’t included in the amendment text or the full statement on the amendment issued by Sanders’ office (so it’s probably on leftists in foreign policy to make sure it does next time).

Conclusion

Not an original idea. This seems in line with narratives adopted by various labor movements across time. But I thought it’d be worth mentioning because from the chart above it looks like the post-Cold war movements had some success.

Thanks for your time,

Stephen (@stephensemler; stephen@securityreform.org)

Find this note useful? Please consider supporting SPRI.