Congress should reject the $901 billion military policy bill

Polygraph | Newsletter n°325 | 10 Dec 2025

IN THIS NEWSLETTER: What’s in the 2026 military policy bill and why your representative and senators should reject it.

*Thank you, William H. and Coleman J., for becoming paid subscribers! Please consider joining them to support my work.

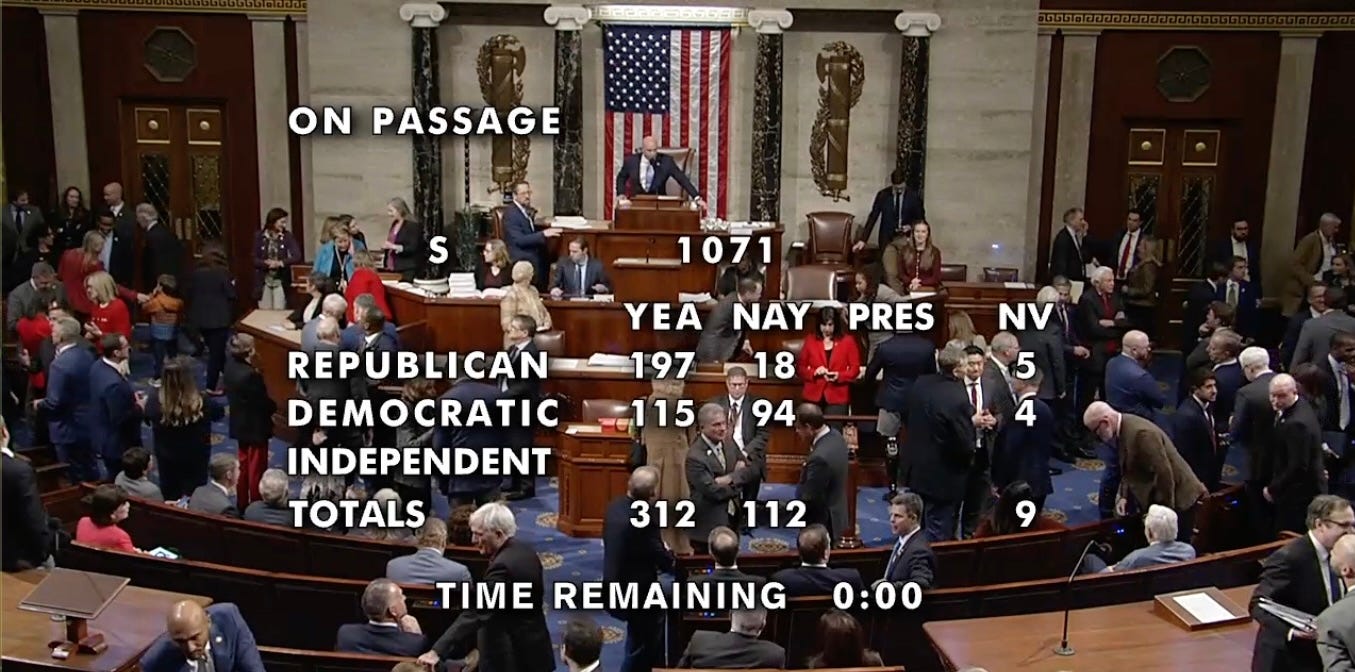

UPDATE (10 Dec 17:46): As Trump starts a war with Venezuela, 312 members of the House — including 115 Democrats — just voted to authorize over $900 billion in military spending.

UPDATE (10 DEC 18:09): Roll call, here.

Summary of the annual military policy bill

The House is scheduled to vote today on a bill that authorizes over $900 billion in military spending. (I’ll update this page accordingly, so be sure to check back here.)

The text of the 2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) — the annual military policy bill — was released Sunday night, and there’s a lot to complain about in its more than 3,000 pages.

For example, Sec. 1706 requires an assessment of the countries restricting arms transfers to Israel over its human rights abuses, which weapons are being withheld, and how the US can “mitigate such gaps.” In other words, the bill says that the US government should function as Israel’s tool for bypassing international arms embargoes. The House Armed Services Committee said this provision “combats antisemitism.” I wish I were kidding.

You won’t find many policies that genuinely align with working-class interests. Sec. 8369, which repeals the devastating Caesar sanctions that indiscriminately punished ordinary Syrians for the last several years, is one of the few bright spots.

Members of Congress will tout the bill’s 3.8% troop pay increase, but not mention the ways the legislation sets up troops to be used as bait or cannon fodder. This includes the high-risk, little-to-no-reward provisions under Sec. 1254 geared toward antagonizing China, including one that instructs the US to “expand the scope and scale of multilateral military exercises,” in the Indo-Pacific, “including more frequent combined maritime operations through the Taiwan Strait and in the South China Sea.”

Corporate interests are represented well. For example, Sec. 803 establishes a pilot program that expands what expenses military contractors can legally bill the government for, including interest payments. Basically, the Pentagon is experimenting with covering contractors’ debt (and other previously unallowable costs).

Corporate interests are also favored based on what’s not in the bill text. Reportedly due to a last-minute arms industry lobbying blitz, “right-to-repair” provisions were stripped from the final version of the NDAA. Right now, military personnel often aren’t legally allowed to fix their own equipment — they’ve got to go back to the contractor for repairs and upkeep. This is a big reason why the operations and maintenance portion of the military budget is larger than all the others, including the accounts for personnel and procurement.1

One reason the lobbying effort to strip the right-to-repair provisions was successful was that the members of Congress who negotiate the final version of the NDAA are often the top recipients of arms industry campaign contributions. They also receive a lot of money from the arms industry lobbyists themselves.2 Among other privileges, this cash makes it a hell of a lot easier to get meetings with members’ offices. I can personally attest to this fact.

Context: a $1 trillion military budget

Today’s vote is effectively a yea-or-nay on a $1 trillion military budget: the $901 billion in the pending National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) is on top of the extra $156 billion in military spending included in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, passed in July.3 The White House said it will use $119 billion of that in 2026, saving the rest for future years. This means that the members of Congress who vote yea/yes on today’s NDAA are signaling their support for a $1.020 trillion military budget, $8 billion more than Trump asked for.

NB: $1.020 trillion is the amount that’s able to be endorsed or rejected today. This amount does not include military-related spending outside the discretionary military budget, including pensions for retired military personnel, military aid funded by the State Department, veterans’ health care and other benefits, DHS, ICE, and other “security spending.”

Should Congress pass the 2026 military policy bill?

No.

The Trump administration is leading us into an Iraq-style war in Venezuela, is using US military forces to occupy US cities, and has pledged to resume nuclear weapons testing. What message would voting for the $901 billion NDAA send to the administration? What policies would a $1.020 trillion military budget enable? Money is policy.

The Pentagon still can’t pass an audit. A trillion-dollar military budget would trigger a historic redistribution of wealth that would primarily benefit the 1%. Social programs are being slashed to fund historic increases in Pentagon spending — the One Big Beautiful Bill Act managed to do both at the same time — per the recommendation of the Commission on the National Defense Strategy: “The ballooning U.S. deficit also poses national security risks. Therefore, increased security spending should be accompanied by additional taxes and reforms to entitlement spending.”

Mitch McConnell (R-KY) recently argued in the Wall Street Journal that “spending more on defense is simply necessary.” (WSJ didn’t disclose the fact that McConnell has accepted $1.2 million in political donations from the arms industry, so I thought I’d mention it here.) McConnell’s wrong — it’s not necessary. People who treat more military spending as the answer to all questions think in terms of theatrics, not outcomes, which leaves no room to reflect on whether their preferred policy is part of the problem.

How much is enough, anyway? Seven out of every ten dollars the world spends on militaries are spent by the United States and its main allies. Military spending worldwide reached $2.7 trillion last year, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Of that total:

37% was by the United States.4

55% was by the US and the 31 other NATO countries.

70% was by the US, the 31 other NATO countries, and the US’s 21 major non-NATO allies — an official designation under US law that does not include security commitments, but indicates a close relationship with the US and entails special privileges, particularly with respect to arms transfers.5

^Alt text for screen readers: US, major US allies spend 70% of global military budget. This stacked column chart displays 2.7 trillion in military spending worldwide, including $997 billion by the United States, $509 billion by US NATO allies, $383 billion by US major non-NATO allies, and $829 billion by the rest of the world. Figures are for 2024. US total includes related funds outside the discretionary military budget, such as pensions and State Department’s military aid. Data: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

SPECIAL THANKS TO: Abe B., Alan F., Alissa Q., Amin, Andrew R., AT., B. Kelly, BartB., BeepBoop, Ben, Ben C.,* Bill S., Bob N., Brett S., Byron D., Carol V., Chris, Chris G., Cole H., Coleman J., D. Kepler, Daniel M., Dave, David J., David S.,* David V.,* David M., Elizabeth R., Emily H.,* Errol S., Foundart, Francis M., Frank R., Gary W., Gladwyn S., Graham P., Griffin R., Hunter S., IBL, Irene B., Isaac, Isaac L., Jacob, James G., James H., James N., Jamie LR., Jcowens, Jeff, Jennifer, Jennifer J., Jessica S., Jerry S., Joe R., John, John, John A., John K., John M., Jonathan S., Joseph B., Joshua R., Julia G., Julian L., Katrina H., Keith B., Kheng L., Lea S., Leah A., Leila CL., Lenore B., Linda B., Linda H., Lindsay, Lindsay S.,* Lora L., Mapraputa, Marie R., Mark L., Mark G., Marvin B., Mary Z., Marty, Matthew H.,* Megan., Melanie B., Michael S., Mitchell P., Nick B., Noah K., Norbert H., Omar A., Omar D.,* Peter M., Phil, Philip L., Ron C., Rosemary K., Sari G., Scarlet, Scott H., Silversurfer, Soh, Springseep, Stan C., TBE, Teddie G., Theresa A., Themadking, Tim C., Timbuk T., Tony L., Tony T., Tyler M., Victor S., Wayne H., William H.,* William P.

* = founding member

-Stephen (Follow me on Instagram, Twitter, and Bluesky)

The right-to-repair issue historically has had a lot to do with McDonald’s constantly out-of-order McFlurry machines.

Now that I’m thinking of it, I’m not sure if political contributions from lobbyists paid by the arms industry are counted as arms industry political contributions by OpenSecrets, the main organization that tracks this stuff. I should ask.

From an official budget scorekeeping perspective, the $156 billion in military spending in the OBBA counts toward 2025, because budget authority for multiyear appropriations is typically counted toward the first year. However, the military spending in the OBBA is only going to be actually put toward certain things — in the form of obligations — beginning in 2026. The White House has said it plans on using $119 billion from that amount in 2026 and the rest in future years. Another technical note: the $901 billion in the NDAA is discretionary spending, while the OBBA funding is mandatory. Typically, mandatory spending makes up a very small portion of overall military spending, mostly going to things like pensions, while nearly all of it (like 98%) is discretionary spending, which Congress approves every year. The mandatory military spending in the OBBA functions like additional discretionary spending, which is why I talk about it in the same breath as the discretionary spending authorized by the NDAA. I know this is a bit confusing. Comment below with any questions and I’ll answer them.

The US total includes military aid funded by the State Department, which is authorized and appropriated outside the NDAA and discretionary military spending bills.

The total for major non-NATO allies in the chart reflects the military budgets of the 21 current major non-NATO allies, including Saudi Arabia (which Trump designated as a major non-NATO ally last month) and Taiwan, which isn’t formally designated as such but has been “treated as though it were designated a major non-NATO ally” under US law since 2002.