House boosts military budget as Pentagon extends failed audit streak to 30 years

Polygraph | Newsletter n°333 | 23 Jan 2026

IN THIS NEWSLETTER: Federal agencies have been required to pass an audit since 1996. The Pentagon still hasn’t — with budget increases like the one the House approved last night, why bother?

*ICYMI: How much aid has the US given Israel? After uncovering over $7 billion in previously unreported funds, this is the most accurate tally of US aid to Israel to date.

*Big thanks to Claudia for becoming a paid subscriber! Please consider joining Claudia and the other Polygraph VIPs thanked at the bottom of each newsletter.

House vote

Last night, the House passed a bill that pushes this year’s military budget past the $1 trillion mark. The legislation garnered the support of 149 Democrats. Just 3% of Democratic voters want to increase military spending, but 70% of House Democrats just voted for an increase.

The question is whether Democrats should be let off the hook for that vote because the Pentagon bill was bundled with two other spending bills. One reason they shouldn’t is that three-quarters of the money in the three-bill “minibus” is military spending. There’s $839 billion for the Pentagon, but only $195 billion for the Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, and $103 billion for the Departments of Transportation and Housing and Urban Development.

Another reason is that military spending enables the performative shows of force that increasingly define Trump’s foreign policy. The scale of these violent and dangerous performances will grow to fit the expanded military budget the House just gave him (pending Senate approval). The aforementioned $839 billion is on top of the $156 billion in military spending included in the Big Beautiful Bill1 and is in addition to the military spending in other 2026 budget bills, including $34 billion from the Energy Department bill (mostly for nuclear weapons); $20 billion from Military Construction and Veterans Affairs; $7 billion from Commerce, Justice, and Science; $3 billion from Homeland Security; $400 million from Transportation; and $50 million from Financial Services. Of the 12 annual spending bills, 7 include military spending.

Taken together, the pending 2026 military budget totals $1.02 trillion. Note that I only counted the money that fits within the US government’s definition of military spending,2 which excludes certain costs of war (e.g., Veterans Affairs budget) and paramilitary forces (e.g., ICE budget).3

A third reason is that this money is controlled by an executive department that can’t pass an audit. The Pentagon doesn’t properly track its spending or resources. This means that House members overwhelmingly approved a historic transfer of wealth without knowing how taxpayer dollars will actually be used.

Naturally, 89% of House Republicans — who last year slashed social welfare in the name of reducing government waste, fraud, and abuse — voted to increase funding for the single largest driver of that waste, fraud, and abuse.

30 years of failed audits

It got lost in the news cycle, but over the holidays, the Pentagon failed its eighth consecutive audit. Sounds bad. But even this framing shortchanges the department’s breathtaking negligence. The Pentagon has had 30 years to pass an audit, and it still hasn’t passed one.

The Chief Financial Officers Act (CFO) of 1990 required 24 major executive branch departments and agencies to prepare annual financial statements and have them audited. However, the CFO Act required only limited financial statements for certain agency activities. The Government Management Reform Act (GMRA) of 1994 filled this gap, directing those 24 CFO Act agencies to prepare agency-wide audited financial statements for fiscal year 1996 by March 1, 1997.4

The Pentagon submitted agency-wide financial statements for audit from 1996–2001, and failed all of them. Technically, they resulted in “disclaimers of opinion” — when an organization’s books are such a mess that there’s not even enough evidence to form an audit opinion. That’s tantamount to failure, but it’s somehow worse than the lowest grade auditors can give (“adverse opinions”). At least in those cases, there are financial records for auditors to evaluate. The Pentagon couldn’t even produce the materials auditors grade. In 2001, Congress decided to spare the Pentagon further humiliation by passing a law allowing the department to skip the annual agency-wide audit beginning in 2002. This was undone by a 2014 law that led to the resumption of full audits in 2018. The Pentagon has failed all eight audits since then, all receiving disclaimers of opinion. If auditors can’t even gather enough evidence to say what specific problems are going on, it’s likely that actual fraud is far greater than reported fraud. So the recently disclosed $10.8 billion in fraud isn’t just the tip of the iceberg, it’s the tip of that tip.

The underlying theory of the CFO Act and GMRA was that adopting private sector-style financial accounting and reporting standards would make federal agencies more efficient and accountable. Financial audits — third-party investigations of an organization’s books — support government accountability by revealing how agencies spend public money and manage the things they purchase.

Is there another system (a complex, if you will) more in need of greater accountability? The Pentagon owns 82% of the federal government’s total physical assets, eats about 50% of the budget Congress passes each year, and sends 54% of its own budget to for-profit companies. It doesn’t know the number, value, or location of all its matériel scattered across the globe on land, sea, and sky. In 2025, the Pentagon couldn’t account for at least 43% of its assets and 64% of its budgetary resources.5 How can Congress or the New York Times claim the military is under-resourced when the Pentagon itself doesn’t know what it already has?

Congress made the problem worse last night by approving a massive increase in military spending. How? Consider the following. The Pentagon couldn’t account for 47% of its assets in 2022 and 43% in 2025 — a modest improvement. However, the Pentagon is missing more stuff now than it was in 2022. Because it acquired more and more assets during the intervening years, the dollar value of the items it couldn’t account for increased by $342 billion, totaling $2 trillion in 2025. So while the share of the assets it can’t account for fell by 9% (or four percentage points), the dollar value of those missing assets increased by 21%. Congress rewards the Pentagon’s incompetence faster than it makes progress on audits.

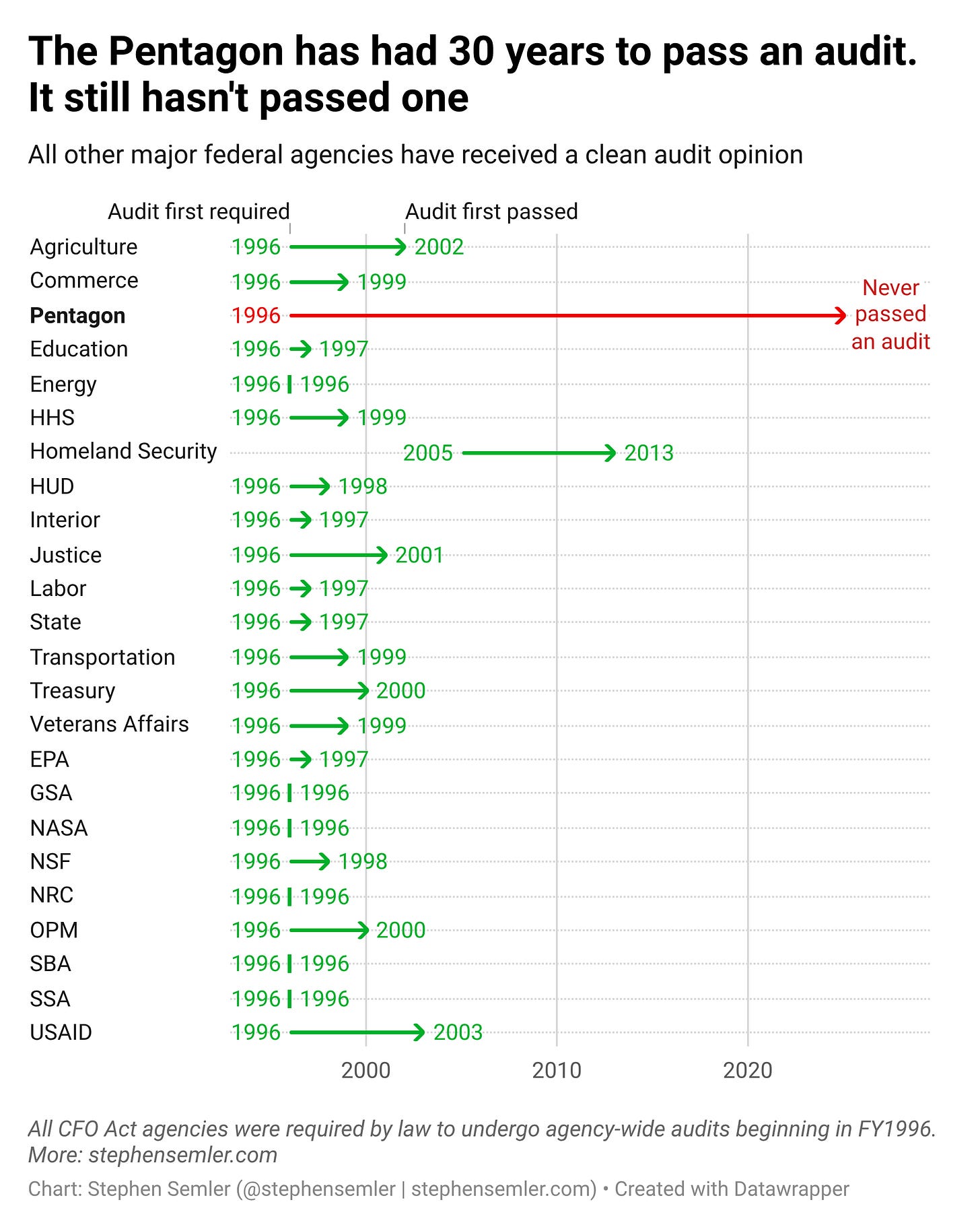

The graph below shows how long it’s taken major federal agencies to pass an audit. (If you’re unsure of any of the acronyms, see here.) After the agency-wide audit requirement kicked in for 1996 (2005 for the Department of Homeland Security), some agencies passed the same year, while others took longer. All told, 23 of the 24 CFO Act agencies have received a clean audit opinion.

On average, it takes a federal agency just under two and a half years to pass an audit. The Pentagon hasn’t passed one in thirty.

^Alt text for screen readers: The Pentagon has had 30 years to pass an audit. It still hasn’t passed one. All other major federal agencies have received a clean audit opinion. This chart shows how many years each agency took to pass an audit. All CFO Act agencies were required by law to undergo agency-wide audits beginning in fiscal year 1996, except for the Department of Homeland Security, which was in 2005. Here is each agency and the first year each one passed an audit: Agriculture, 2002; Commerce, 1999; Pentagon, never passed an audit; Education, 1997; Energy, 1996; HHS, 1999; Homeland Security, 2013; HUD, 1998; Interior, 1997; Justice, 2001; Labor, 1997; State, 1997; Transportation, 1999; Treasury, 2000; Veterans Affairs, 1999; EPA, 1997; GSA, 1996; NASA, 1996; NSF, 1998; NRC, 1996; OPM, 2000; SBA, 1996; SSA, 1996; USAID, 2003.

SPECIAL THANKS TO: Abe B., Alan F., Alissa Q., Amin, Andrew R., AT., B. Kelly, Bart B., BeepBoop, Ben, Ben C.,* Bill S., Bob N., Brett S., Byron D., Carol V., Catherine L., Chris, Chris G., Claudia, Cole H., Coleman J., D. Kepler, Daniel M., Dave, David J., David S.,* David V.,* David M., Dharna N., Elizabeth R., Emily H.,* Errol S., Foundart, Francis M., Frank R., Fred R., Gary W., Gladwyn S., Graham P., Griffin R., Hunter S., IBL, Irene B., Isaac, Isaac L., Jacob, James G., James H., James N., Jamie LR., Jcowens, Jeff, Jennifer, Jennifer J., Jessica S., Jerry S., Joe R., John, John, John A., John K., John M., Jonathan S., Joseph B., Joshua R., Julia G., Julian L., Katrina H., Keith B., Kheng L., Lea S., Leah A., Leila CL., Lenore B., Linda B., Linda H., Lindsay, Lindsay S.,* Lora L., Mapraputa, Marie R., Mark L., Mark G., Marvin B., Mary Z., Marty, Matthew H.,* Megan., Melanie B., Michael S., Mitchell P., Nick B., Noah K., Norbert H., Omar A., Omar D.,* Peter M., Phil, Philip L., Ron C., Rosemary K., Sari G., Scarlet, Scott H., Silversurfer, Soh, Springseep, Stan C., TBE, Teddie G., Theresa A., Themadking, Tim C., Timbuk T., Tony L., Tony T., Tyler M., Victor S., Wayne H., William H.,* William P.

* = founding member

-Stephen (Follow me on Instagram, Twitter, and Bluesky)

$119 billion of which the administration said it will use this year.

Funding under budget function 050, also referred to as “security” or “national defense” spending.

I’m also only counting budgetary costs, and not economic or moral costs, for example.

Title IV, Section 405(a): “Not later than March 1 of 1997 and each year thereafter, the head of each executive agency identified in section 901(b) of this title shall prepare and submit to the Director of the Office of Management and Budget an audited financial statement for the preceding fiscal year, covering all accounts and associated activities of each office, bureau, and activity of the agency.”

Specifically, I’m referring to the entities within the Pentagon that received a disclaimer of opinion that, together, accounted for 43% of the Pentagon’s assets and 64% of its budgetary resources. Others may use a different measure for the percentage of assets that can’t be accounted for.